J. Södergren Advokatbyrå AB

Specialister på mänskliga rättigher

Resumé

Statistical Summary – Jan Södergren

January 2026

Summary

Based on searches in HUDOC (the European Court of Human Rights database) and other materials, the following cases have been identified where Jan Södergren (J. Södergren) has acted as representative/counsel:

-

8 cases examined on the merits or achieving success through interim measures

-

7 cases with success (6 with violation findings, 1 struck out after interim measures)

-

1 case examined on the merits without violation finding

-

1 Grand Chamber case (Söderman v. Sweden) – reversed from 4-3 loss in Chamber to 16-1 victory

-

1 case with interim measures (Rule 39) leading to permanent residence permit

-

All cases concern unique legal issues with substantially different circumstances

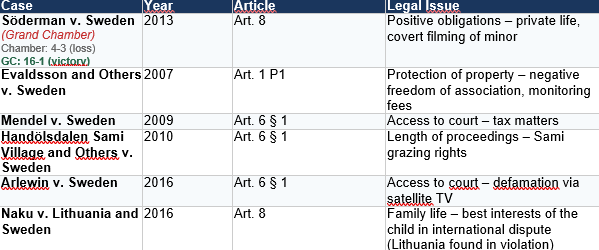

Cases where violations were found

Case struck out after interim measures (Rule 39)

Note: The Girmay case did not result in a judgment because the Migration Board granted a permanent residence permit after the European Court of Human Rights indicated interim measures under Rule 39. The case was therefore struck out. Such cases are normally not published as full judgments in HUDOC, but the interim measures decision demonstrates that the Court assessed there to be a risk of irreparable harm if the deportation were executed.

Case examined on the merits without violation finding

Note: Having a case communicated and examined on the merits by the European Court of Human Rights is in itself significant. The vast majority of applications are declared inadmissible at an early stage by a single judge. The fact that this case reached examination on the merits demonstrates that the legal issues were considered sufficiently serious to warrant full consideration by a Chamber.

Comparative Analysis

The Court's inadmissibility statistics – the rigorous filtering process

To understand the significance of having a case examined on the merits, one must consider the European Court of Human Rights' inadmissibility statistics. According to the Court's own official information, approximately 90% of all applications received are rejected as inadmissible. In some years, this figure has been as high as 95%.

Concrete figures from 2024:

-

25,990 applications were declared inadmissible or struck out

-

Of these, 22,210 were handled by a single judge

-

Only 1,102 judgments were delivered

Corresponding figures from 2022:

-

35,402 applications were declared inadmissible or struck out

-

Of these, 30,585 were handled by a single judge

-

Only 1,163 judgments were delivered

This means that for every judgment delivered, approximately 25–35 applications are rejected. The proportion of applications that actually reach judgment is only approximately 3–4%.

The filtering process in practice: The initial review is conducted summarily. A young case lawyer studies the file and prepares it for a single judge. The single judge can reject the application outright – without the State even being required to submit observations – through a decision that is final and cannot be appealed. Only if the application passes this stage is it communicated to the State.

What this means for the statistics: Having 8 cases examined on the merits over a professional career of more than 30 years – of which 7 were successful – must be viewed against the background that 96–97% of all applications never get that far. It is not about quantity, but about managing to pass through one of the most rigorous filters in international adjudication.

The significance of interim measures (Rule 39)

Interim measures under Rule 39 are an extraordinary measure that the European Court of Human Rights only indicates when there is an imminent risk of irreparable harm – typically risk of torture, inhuman treatment or death. According to the Court's statistics, interim measures are only granted in a minority of cases where such measures are requested.

Obtaining interim measures and subsequently seeing the State grant a residence permit is in practice a complete success for the applicant – the case never reaches judgment because the dispute is resolved. It is an acknowledgment that the original deportation was problematic from a Convention perspective.

On Swedish Convention compliance

Sweden enjoys an international reputation for good compliance with the rule of law, which in practice affects the processing of applications in Strasbourg. The initial review is conducted summarily – often by a young case lawyer who studies the file, after which a single judge may declare the application inadmissible without the State even being required to submit observations.

However, this reputation has been questioned. Sweden's actual compliance with the Convention – particularly regarding the quality and depth of domestic judicial review when Convention issues arise – has been criticized by both academics and practitioners. It can be argued that Sweden's good reputation favours the State in the initial filtering process rather than reflecting a consistent respect for Convention rights in domestic legal practice.

Swedish lawyers

There are no public statistics on which lawyers have had the most cases before the European Court of Human Rights. The HUDOC database lacks a search function for counsel that would make it possible to easily compile such statistics.

What can be established is that the number of Swedish cases that reach full examination by the European Court of Human Rights is relatively low, largely due to the summary processing at the application stage. For a Swedish lawyer to have eight different cases examined on the merits or achieving success through interim measures – in entirely different areas of law – is unique.

Grand Chamber cases

Under Article 43 of the European Convention, a party may, "in exceptional cases", request that a case be referred to the Grand Chamber within three months of the Chamber judgment. A panel of five judges considers whether the case raises a serious question affecting the interpretation or application of the Convention, or a serious issue of general importance. According to the Court's statistics, only approximately 5-6% of all referral requests are accepted – the requirement of "exceptional cases" is thus strictly applied.

Söderman v. Sweden was a case of fundamental importance that resulted in a significant development of the Court's case-law regarding positive obligations under Article 8. The case was first lost in the Chamber by the narrowest possible margin (4 votes to 3). Following referral to the Grand Chamber, the case was won by an overwhelming majority (16 votes to 1) – a remarkable reversal that underscores that the applicant's legal arguments were correct and that the Chamber majority was wrong.

No other Swedish lawyer has, as far as can be determined, brought a Swedish case to the Grand Chamber as sole responsible counsel.

Nordic counsel

Similar statistics are not available for other Nordic countries. The Nordic countries (Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Finland, Iceland) generally have low numbers of cases before the European Court of Human Rights compared to countries such as Turkey, Russia, Ukraine and Romania.

Europe generally

In countries with systematic violations (for example Turkey, Russia before its withdrawal, Ukraine), there are lawyers who have had hundreds of cases. These cases, however, often concern the same type of violation:

-

Torture and inhuman treatment (Art. 3)

-

Unreasonable detention and length of proceedings (Art. 5, 6)

-

Freedom of expression and press freedom (Art. 10)

-

Restitution of property confiscated under communism

Comparing such "repetitive" cases with eight entirely different legal issues – positive obligations under Art. 8, protection of property linked to freedom of association, access to court in tax matters, length of proceedings in land rights disputes, jurisdiction in cross-border defamation, family law disputes, deportation with risk of trafficking, and compulsory care of children – does not provide a fair comparison.

Legislative Consequences

Two of the cases have led to concrete legislative measures in Sweden, underscoring that these were not merely individual victories but system-changing precedents.

Söderman v. Sweden → New criminal offence

As a direct consequence of the case – and the gap in Swedish law identified by the European Court of Human Rights – the offence of "kränkande fotografering" (intrusive photography) was introduced in Chapter 4, Section 6a of the Swedish Criminal Code (Brottsbalken) on 1 July 2013 (Government Bill 2012/13:69). The Swedish Supreme Court had already signalled in NJA 2008 p. 946 that Swedish protection against covert filming was inadequate and that its compatibility with the European Convention could be questioned. The Grand Chamber judgment confirmed this and compelled legislative action.

The criminal provision means that anyone who unlawfully and covertly uses technical equipment to capture images of a person who is inside a residence, in a toilet, changing room or similar space is guilty of intrusive photography and may be sentenced to a fine or imprisonment for up to two years.

Arlewin v. Sweden → Constitutional amendment

The case required Sweden to amend the Fundamental Law on Freedom of Expression (Yttrandefrihetsgrundlagen, YGL) – one of Sweden's four constitutional laws. Constitutional amendments require, under Chapter 8, Section 14 of the Instrument of Government, two identical parliamentary decisions with a general election in between, making the process significantly more demanding than ordinary legislation.

The European Court of Human Rights held in its judgment of 1 March 2016 that Sweden had violated Article 6(1) of the Convention (right of access to court) because it was impossible to hold anyone accountable in Sweden for defamation in a TV3 programme that was formally broadcast from the United Kingdom but was in all essential respects Swedish in nature.

The constitutional amendment was adopted through:

-

First parliamentary decision: 11 May 2022

-

General election: September 2022

-

Second parliamentary decision: 2022/23 parliamentary session (Committee Report 2022/23:KU6)

The amendment extends the territorial scope of the Fundamental Law on Freedom of Expression to include certain satellite broadcasts that formally originate from abroad but have a very strong Swedish connection. This means that defamation cases and similar matters can now be tried in Swedish courts even when the programme is technically broadcast from abroad.

The significance of the legislative consequences

For an individual lawyer's litigation to result in new criminal legislation and a constitutional amendment is exceptionally rare. It demonstrates that these cases were not merely about individual clients' rights but identified systemic deficiencies in Swedish law that required action at the legislative level. In the Arlewin case, moreover, the most rigorous form of legislation was required – constitutional amendment with two decisions and an intervening election.

Conclusion

Jan Södergren's track record before the European Court of Human Rights is unique among Swedish lawyers:

-

Eight cases examined on the merits or achieving success through interim measures

-

Seven cases with success (six with violation findings, one with interim measures leading to permanent residence permit)

-

One Grand Chamber case – very rare for Swedish counsel

-

One case with interim measures granted (Rule 39) – extraordinary measure in cases of risk of irreparable harm

-

All cases concern unique legal issues with fundamentally different circumstances

-

Spanning multiple Convention articles (Art. 3, Art. 6, Art. 8, Art. 1 P1)

No other Swedish lawyer has been identified as having a comparable track record in terms of the number of different cases examined on the merits, a Grand Chamber case, and a case with interim measures granted. Among Nordic counsel, this combination is likely to be very rare.

Methodological Note

This summary is based on:

-

Searches in HUDOC (hudoc.echr.coe.int)

-

Published judgments where "J. Södergren" or "Jan Södergren" is listed as representative/counsel

-

Academic and legal analyses of the relevant cases

-

Documentation provided by counsel (Girmay case, application no. 80545/12)

HUDOC's search function does not allow systematic searches by counsel, which means that a complete comparison with other lawyers is not possible without manual review of all judgments. Cases that are struck out after interim measures are normally not published as full judgments in HUDOC.